The replicability of psychological research is surprisingly low. Why? In this blog post I present new evidence showing that questionable research practices contributed to failures to replicate psychological effects.

Quick recap. A recent publication in Science claims that only around 40% of psychological findings are replicable, based on 100 replication attempts in the Reproducibility Project Psychology (Open Science Collaboration, 2015). A few months later, a critical commentary in the same journal made all sorts of claims, including that the surprisingly low 40% replication success rate is due to replications having been unfaithful to the original studies’ methods (Gilbert et al., 2016). A little while later, I published an article in Psychonomic Bulletin & Review re-analysing the data by the 100 replication teams (Kunert, 2016). I found evidence for questionable research practices being at the heart of failures to replicate, rather than the unfaithfulness of replications to original methods.

However, my previous re-analysis depended on replication teams having done good work. In this blog post I will show that even when just looking at the original studies in the Reproducibility Project: Psychology one cannot fail to notice that questionable research practices were employed by the original discoverers of the effects which often failed to replicate. The reanalysis I will present here is based on the caliper test introduced by Gerber and colleagues (Gerber & Malhotra, 2008; Gerber et al., 2010).

The idea of the caliper test is simple. The research community has decided that an entirely arbitrary threshold of p = 0.05 distinguishes between effects which might just be due to chance (p > 0.05) and effects which are more likely due to something other than chance (p < 0.05). If researchers want to game the system they slightly rig their methods and analyses to push their p-values just below the arbitrary border between ‘statistical fluke’ and ‘interesting effect’. Alternatively, they just don’t publish anything which came up p > 0.05. Such behaviour should lead to an unlikely amount of p-values just below 0.05 compared to just above 0.05.

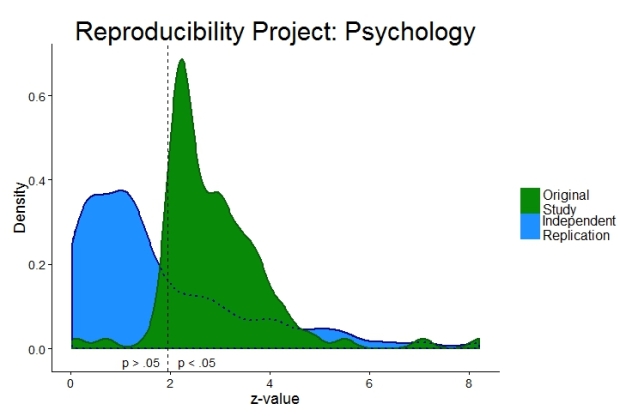

The figure below shows the data of the Reproducibility Project: Psychology. On the horizontal axis I plot z-values which are related to p-values. The higher the z-value the lower the p-value. On the vertical axis I just show how many z-values I found in each range. The dashed vertical line is the arbitrary threshold between p < .05 (significant effects on the right) and p > .05 (non-significant effects on the left).

The independent replications in blue show many z-values left of the dashed line, i.e. replication attempts which were unsuccessful. Otherwise the blue distribution is relatively smooth. There is certainly nothing fishy going on around the arbitrary p = 0.05 threshold. The blue curve looks very much like what I would expect psychological research to be if questionable research practices did not exist.

However, the story is completely different for the green distribution representing the original effects. Just right of the arbitrary p = 0.05 threshold there is a surprising clustering of z-values. It’s as if the human mind magically leads to effects which are just about significant rather than just about not significant. This bump immediately to the right of the dashed line is a clear sign that original authors used questionable research practices. This behaviour renders psychological research unreplicable.

For the expert reader, the formal analysis of the caliper test is shown in the table below using both a Bayesian analysis and a classical frequentist analysis. The conclusion is clear. There is no strong evidence for replication studies failing the caliper test, indicating that questionable research practices were probably not employed. The original studies do not pass the caliper test, indicating that questionable research practices were employed.

| over caliper

(significant) |

below caliper (non-sign.) | Binomial test | Bayesian proportion test | posterior median

[95% Credible Interval]1 |

|

|

10 % caliper (1.76 < z < 1.96 versus 1.96 < z < 2.16) |

|||||

| Original | 9 | 4 | p = 0.267 | BF10 = 1.09 | 0.53

[-0.36; 1.55] |

| Replication | 3 | 2 | p = 1 | BF01 = 1.30 | 0.18

[-1.00; 1.45] |

|

15 % caliper (1.67 < z < 1.96 versus 1.96 < z < 2.25) |

|||||

| Original | 17 | 4 | p = 0.007 | BF10 = 12.9 | 1.07

[0.24; 2.08] |

| Replication | 4 | 5 | p = 1 | BF01 = 1.54 | -0.13

[-1.18; 0.87] |

|

20 % caliper (1.76 < z < 1.57 versus 1.96 < z < 2.35) |

|||||

| Original | 29 | 4 | p < 0.001 | BF10 = 2813 | 1.59

[0.79; 2.58] |

| Replication | 5 | 5 | p = 1 | BF01 = 1.64 | 0.00

[-0.99; 0.98] |

1Based on 100,000 draws from the posterior distribution of log odds.

As far as I know, this is the first analysis showing that data from the original studies of the Reproducibility Project: Psychology point to questionable research practices [I have since been made aware of others, see this comment below]. Instead of sloppy science on the part of independent replication teams, this analysis rather points to original investigators employing questionable research practices. This alone could explain the surprisingly low replication rates in psychology.

Psychology failing the caliper test is by no means a new insight. Huge text-mining analyses have shown that psychology as a whole tends to fail the caliper test (Kühberger et al., 2013, Head et al., 2015). The analysis I have presented here links this result to replicability. If a research field employs questionable research practices (as indicated by the caliper test) then it can no longer claim to deliver insights which stand the replication test (as indicated by the Reproducibility Project: Psychology).

It is time to get rid of questionable research practices. There are enough ideas for how to do so (e.g., Asendorpf et al., 2013; Ioannidis, Munafò, Fusar-Poli, Nosek, & Lakens, 2014). The Reproducibility Project: Psychology shows why there is no time to waste: it is currently very difficult to distinguish an interesting psychological effect from a statistical fluke. I doubt that this state of affairs is what psychological researchers get paid for.

PS: full R-code for recreating all analyses and figures is posted below. If you find mistakes please let me know.

PPS: I am indebted to Jelte Wicherts for pointing me to this analysis.

Update 25/4/2015:

I adjusted text to clarify that caliper test cannot distinguish between many different questionable research practices, following tweet by Daniël Lakens.

I toned down the language somewhat following tweet by Daniel Bennett.

I added reference to Uli Schimmack’s analysis by linking his comment.

— — —

Asendorpf, J., Conner, M., De Fruyt, F., De Houwer, J., Denissen, J., Fiedler, K., Fiedler, S., Funder, D., Kliegl, R., Nosek, B., Perugini, M., Roberts, B., Schmitt, M., van Aken, M., Weber, H., & Wicherts, J. (2013). Recommendations for Increasing Replicability in Psychology European Journal of Personality, 27 (2), 108-119 DOI: 10.1002/per.1919

Gerber, A., & Malhotra, N. (2008). Publication Bias in Empirical Sociological Research: Do Arbitrary Significance Levels Distort Published Results? Sociological Methods & Research, 37 (1), 3-30 DOI: 10.1177/0049124108318973

Gerber, A., Malhotra, N., Dowling, C., & Doherty, D. (2010). Publication Bias in Two Political Behavior Literatures American Politics Research, 38 (4), 591-613 DOI: 10.1177/1532673X09350979

Gilbert, D., King, G., Pettigrew, S., & Wilson, T. (2016). Comment on “Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science” Science, 351 (6277), 1037-1037 DOI: 10.1126/science.aad7243

Head ML, Holman L, Lanfear R, Kahn AT, & Jennions MD (2015). The extent and consequences of p-hacking in science. PLoS biology, 13 (3) PMID: 25768323

Ioannidis JP, Munafò MR, Fusar-Poli P, Nosek BA, & David SP (2014). Publication and other reporting biases in cognitive sciences: detection, prevalence, and prevention. Trends in cognitive sciences, 18 (5), 235-41 PMID: 24656991

Kühberger A, Fritz A, & Scherndl T (2014). Publication bias in psychology: a diagnosis based on the correlation between effect size and sample size. PloS one, 9 (9) PMID: 25192357

Kunert R (2016). Internal conceptual replications do not increase independent replication success. Psychonomic bulletin & review PMID: 27068542

Open Science Collaboration (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science Science, 349 (6251) DOI: 10.1126/science.aac4716

— — —

################################################################################################################## # Script for article "Questionable research practices in original studies of Reproducibility Project: Psychology"# # Submitted to Brain's Idea (status: published) # # Responsible for this file: R. Kunert (rikunert@gmail.com) # ################################################################################################################## ########################################################################################################################################################################################## #----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- #Figure 1: p-value density # source functions if(!require(httr)){install.packages('httr')} library(httr) info <- GET('https://osf.io/b2vn7/?action=download', write_disk('functions.r', overwrite = TRUE)) #downloads data file from the OSF source('functions.r') if(!require(devtools)){install.packages('devtools')} #RPP functions library(devtools) source_url('https://raw.githubusercontent.com/FredHasselman/toolboxR/master/C-3PR.R') in.IT(c('ggplot2','RColorBrewer','lattice','gridExtra','plyr','dplyr','httr','extrafont')) if(!require(BayesFactor)){install.packages('BayesFactor')} #Bayesian analysis library(BayesFactor) if(!require(BEST)){install.packages('BEST')} #distribution overlap library(BEST)#requires JAGS version 3 if(!require(RCurl)){install.packages('RCurl')} # library(RCurl)# #the following few lines are an excerpt of the Reproducibility Project: Psychology's # masterscript.R to be found here: https://osf.io/vdnrb/ # Read in Tilburg data info <- GET('https://osf.io/fgjvw/?action=download', write_disk('rpp_data.csv', overwrite = TRUE)) #downloads data file from the OSF MASTER <- read.csv("rpp_data.csv")[1:167, ] colnames(MASTER)[1] <- "ID" # Change first column name to ID to be able to load .csv file #for studies with exact p-values id <- MASTER$ID[!is.na(MASTER$T_pval_USE..O.) & !is.na(MASTER$T_pval_USE..R.)] #FYI: turn p-values into z-scores #z = qnorm(1 - (pval/2)) #prepare data point for plotting dat_vis <- data.frame(p = c(MASTER$T_pval_USE..O.[id], MASTER$T_pval_USE..R.[id], MASTER$T_pval_USE..R.[id]), z = c(qnorm(1 - (MASTER$T_pval_USE..O.[id]/2)), qnorm(1 - (MASTER$T_pval_USE..R.[id]/2)), qnorm(1 - (MASTER$T_pval_USE..R.[id]/2))), Study_set= c(rep("Original Publications", length(id)), rep("Independent Replications", length(id)), rep("zIndependent Replications2", length(id)))) #prepare plotting colours etc cols_emp_in = c("#1E90FF","#088A08")#colour_definitions of area cols_emp_out = c("#08088a","#0B610B")#colour_definitions of outline legend_labels = list("Independent\nReplication", "Original\nStudy") #execute actual plotting density_plot = ggplot(dat_vis, aes(x=z, fill = Study_set, color = Study_set, linetype = Study_set))+ geom_density(adjust =0.6, size = 1, alpha=1) + #density plot call scale_linetype_manual(values = c(1,1,3)) +#outline line types scale_fill_manual(values = c(cols_emp_in,NA), labels = legend_labels)+#specify the to be used colours (outline) scale_color_manual(values = cols_emp_out[c(1,2,1)])+#specify the to be used colours (area) labs(x="z-value", y="Density")+ #add axis titles ggtitle("Reproducibility Project: Psychology") +#add title geom_vline(xintercept = qnorm(1 - (0.05/2)), linetype = 2) + annotate("text", x = 2.92, y = -0.02, label = "p < .05", vjust = 1, hjust = 1)+ annotate("text", x = 1.8, y = -0.02, label = "p > .05", vjust = 1, hjust = 1)+ theme(legend.position="none",#remove legend panel.grid.major = element_blank(), panel.grid.minor = element_blank(), panel.border = element_blank(), axis.line = element_line(colour = "black"),#clean look text = element_text(size=18), plot.title=element_text(size=30)) density_plot #common legend #draw a nonsense bar graph which will provide a legend legend_labels = list("Independent\nReplication", "Original\nStudy") dat_vis <- data.frame(ric = factor(legend_labels, levels=legend_labels), kun = c(1, 2)) dat_vis$ric = relevel(dat_vis$ric, "Original\nStudy") nonsense_plot = ggplot(data=dat_vis, aes(x=ric, y=kun, fill=ric)) + geom_bar(stat="identity")+ scale_fill_manual(values=cols_emp_in[c(2,1)], name=" ") + theme(legend.text=element_text(size=18)) #extract legend tmp <- ggplot_gtable(ggplot_build(nonsense_plot)) leg <- which(sapply(tmp$grobs, function(x) x$name) == "guide-box") leg_plot <- tmp$grobs[[leg]] #combine plots grid.arrange(grobs = list(density_plot,leg_plot), ncol = 2, widths = c(2,0.4)) #caliper test according to Gerber et al. #turn p-values into z-values z_o = qnorm(1 - (MASTER$T_pval_USE..O.[id]/2)) z_r = qnorm(1 - (MASTER$T_pval_USE..R.[id]/2)) #How many draws are to be taken from posterior distribution for BF and Credible Interval calculations? The more samples the more precise the estimate and the slower the calculation. draws = 10000 * 10#BayesFactor package standard = 10000 #choose one of the calipers #z_c = c(1.76, 2.16)#10% caliper #z_c = c(1.67, 2.25)#15% caliper #z_c = c(1.57, 2.35)#20% caliper #calculate counts print(sprintf('Originals: over caliper N = %d', sum(z_o <= z_c[2] & z_o >= 1.96))) print(sprintf('Originals: under caliper N = %d', sum(z_o >= z_c[1] & z_o <= 1.96))) print(sprintf('Replications: over caliper N = %d', sum(z_r <= z_c[2] & z_r >= 1.96))) print(sprintf('Replications: under caliper N = %d', sum(z_r >= z_c[1] & z_r <= 1.96))) #formal caliper test: originals #Bayesian analysis bf = proportionBF(sum(z_o <= z_c[2] & z_o >= 1.96), sum(z_o >= z_c[1] & z_o <= z_c[2]), p = 1/2) sprintf('Bayesian test of single proportion: BF10 = %1.2f', exp(bf@bayesFactor$bf))#exponentiate BF10 because stored as natural log #sample from posterior samples_o = proportionBF(sum(z_o <= z_c[2] & z_o >= 1.96), sum(z_o >= z_c[1] & z_o <= z_c[2]), p = 1/2, posterior = TRUE, iterations = draws) plot(samples_o[,"logodds"]) sprintf('Posterior Median = %1.2f [%1.2f; %1.2f]', median(samples_o[,"logodds"]),#Median quantile(samples_o[,"logodds"], 0.025),#Lower edge of 95% Credible Interval quantile(samples_o[,"logodds"], 0.975))#Higher edge of 95% Credible Interval #classical frequentist test bt = binom.test(sum(z_o <= z_c[2] & z_o >= 1.96), sum(z_o >= z_c[1] & z_o <= z_c[2]), p = 1/2) sprintf('Binomial test: p = %1.3f', bt$p.value)# #formal caliper test: replications bf = proportionBF(sum(z_r <= z_c[2] & z_r >= 1.96), sum(z_r >= z_c[1] & z_r <= z_c[2]), p = 1/2) sprintf('Bayesian test of single proportion: BF01 = %1.2f', 1/exp(bf@bayesFactor$bf))#exponentiate BF10 because stored as natural log, turn into BF01 #sample from posterior samples_r = proportionBF(sum(z_r <= z_c[2] & z_r >= 1.96), sum(z_r >= z_c[1] & z_r <= z_c[2]), p = 1/2, posterior = TRUE, iterations = draws) plot(samples[,"logodds"]) sprintf('Posterior Median = %1.2f [%1.2f; %1.2f]', median(samples_r[,"logodds"]),#Median quantile(samples_r[,"logodds"], 0.025),#Lower edge of 95% Credible Interval quantile(samples_r[,"logodds"], 0.975))#Higher edge of 95% Credible Interval #classical frequentist test bt = binom.test(sum(z_r <= z_c[2] & z_r >= 1.96), sum(z_r >= z_c[1] & z_r <= z_c[2]), p = 1/2) sprintf('Binomial test: p = %1.3f', bt$p.value)# #possibly of interest: overlap of posteriors #postPriorOverlap(samples_o[,"logodds"], samples_r[,"logodds"])#overlap of distribitions

Nice post!

Would it be interesting to make a plot of the original studies that do subsequently replicate and another plot of the original studies that do not replicate? I wonder if the arbitrary .05 threshold is even more notable in the studies that subsequently fail to replicate.

Good idea. Do you know enough coding with R to just do it yourself? The code at the end of my post should be a good starting point.

The use of the Caliper Test is a novel contribution, but the histogram of of z-scores and the demonstration that the original studies of the OSC RP:P were produced with the help of QRPs is not new.

https://replicationindex.wordpress.com/2015/09/03/comparison-of-php-curve-predictions-and-outcomes-in-the-osf-reproducibility-project-social-psychology-part-1/

https://replicationindex.wordpress.com/2015/09/05/comparison-of-php-curve-predictions-and-outcomes-in-the-osf-reproducibility-project-part-2-cognitive-psychology/

https://replicationindex.wordpress.com/2016/02/26/reported-success-rates-actual-success-rates-and-publication-bias-in-psychology-honoring-sterling-et-al-1995/

A difference between the Caliper Test and my approach is that I also use the distribution of z-scores after selection for significance to estimate the reproducibility of published results. My analyses predicts that results from cognitive psychology have higher reproducibility than those from social psychology and this prediction was confirmed in the actual replication studies.

Not convincing for me, most likely surely is condition “publish if p > 0.05”. This publication bias seems simpler explanation than dodgy practice. Dodgy practice not ruled out at all I hasten to add, but I cannot see this graph as evidence for that.

Thanks for commenting.

I explicitly acknowledge that publication bias can account for these results: ‘Alternatively, they just don’t publish anything which came up p > 0.05.’

I count publication bias as one of the questionable research practices plaguing psychology (see Kunert, 2016 reference in the post). Why? Because it distorts the scientific record. Moreover, there is evidence that publication bias originates with researchers rather than with journals (Franco et al., 2014, 2016). So, I believe it can be grouped with other practices distorting the scientific record. I call such practices ‘questionable research practices’.

Franco, A., Malhotra, N., & Simonovits, G. (2014). Publication bias in the social sciences: Unlocking the file drawer. Science, 345(6203), 1502–1505. doi:10.1126/science.1255484

Franco, A., Malhotra, N., & Simonovits, G. (2016). Underreporting in psychology experiments: Evidence from a study registry. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7(1), 8–12. doi:10.1177/1948550615598377

Thanks for your input and clarification. One thing I would add, however: I think it is important to differentiate QRPs (questionable research practices) from QPPs (questionable publication practices). QRPs imply unethical behavior on the part of the researcher who published the original study, whereas publication bias–which I would categorize as a QPP–does not.

QRPs are the result of researchers being loose with the data, HARKing their results, etc. Publication bias could occur absent these types of QRPs. In other words, researchers could do everything right and not engage in QRPs (such as HARKing, etc.), and if publication bias exists on the part of editors, reviewers, etc., the results would look similar to what you found.

I think the publication bias part needs to be emphasized more. As you note, the graph above could be explained that way. Just in terms of the information contained in a collection of studies, much of it is removed. Your graph says that, if I see a p-value <0.5, now I also know that I'm only going to see papers that have p-values <0.5 (with a few exceptions). Without knowledge of how many studies are to the left of that boundary, I have little information regarding the effect, unless a given study has a really big sample or the p-value is very small.

Thank you for drawing attention to this. How large a research grant can you get for replication of published studies? My experience was not much, maybe things have changed? So, little replication combined with new studies that are confirmatory of author’s theories means we don’t get to learn what doesn’t work (formally).

I like the distinction that Matthewgrizzard made in the comments about QRP and QPP – I think that the QPP can be an engine for QRP and I’d lik eto offer a QRP2: Questionable Research Proposals. Attention could also be directed to the responsibility that funding organizations have to vet/grant funds.

Playing devil’s advocate slightly, could the choice of which studies to replicate be correlated with p-values? e.g. the decision was to replicate interesting studies, which would tend to have p<0.05.

Thanks for commenting Bob O’H

The strategy behind the choice of studies to replicate is laid out in the Science publication by the Open Science Collaboration (2015). I see no reason to expect a correlation between inclusion probability and original study p-value. It would be possible to do such an analysis. If you do, please let me know; would be interesting to see how representative the 100 studies which were replicated were.

Open Science Collaboration. (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of

psychological science. Science, 349(6251), aac4716. doi:10.1126/

science.aac4716

Someone should launch a journal called .075, advertising its willingness to accept papers showing results where p .05 — I reckon it would do quite well.